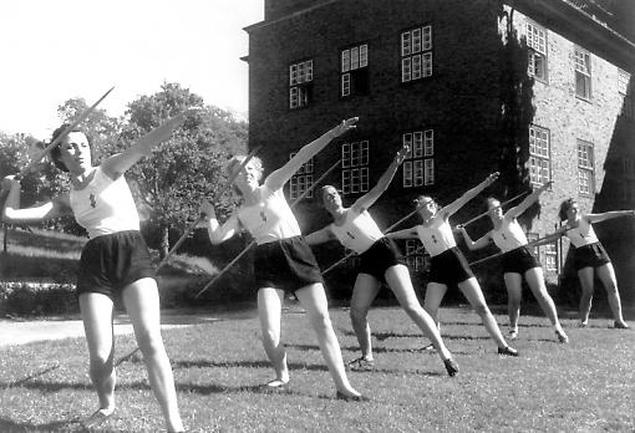

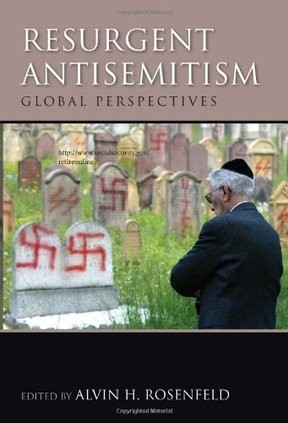

The Inquisitr, October 18, 2013 Recently, a new book, Demonizing Israel and the Jews by Dr. Manfred Gerstenfeld, sent shock waves across Europe by revealing the frightening levels of anti-Semitism and vicious condemnation of Israel taking place in the European Union. Not since 1938 has Europe witnessed such a virulent outbreak of open hatred for the Jewish people. Jews are leaving Europe in record numbers, and in city after city, where Jewish communities once thrived, people have packed their bags and fled to Israel, Canada or the United States. From Paris to Malmo, old Jewish homes are standing empty, as family after family leaves the land of their birth to escape the memories of 1800 years of persecution and death. For those who remain behind, daily life is constant burden and an awful reminder of a time, only 85 years ago, when Jews were forced to wear yellow stars and herded into cattle cars by the millions to be gassed and burned. Now, in the year 2013, Jews are once again spat on and kicked for daring to wear a Kippah on a European street, “Dirty Jew, Hitler should have finished the job” echoes in their ears as they run for cover. Ancient Jewish gravestones are covered with Swastikas and Israeli flags are torn to shreds by ravening crowds of protesters screaming their hatred for the Jewish state. Rather than dwell in despair on the horrors of Jewish life in Modern Europe, we invited Dr. Gerstenfeld here today to explain how and why this is happening and to gain an understanding of what can be done about it. Does hope still remain for the Jews of Europe or are we on the verge of a second Holocaust? Is Israel facing nuclear annihilation or can the Jewish state finally take its place as an equal partner among the nations of the world. After all the horrors of World War Two and the extermination of half of the world’s Jews, we are witnessing a re-birth of the same ugly hatred. What does this tell us about the human soul and the future of our species? Wolff Bachner: Dr. Gerstenfeld, welcome to The Inquisitr once again. Today, we are here to discuss one of the most disturbing and least discussed phenomenons of the 21st century, the re-birth of virulent Jew hate and anti-Israelism that has become prevalent throughout Europe. In your new book, Demonizing Israel and the Jews, you make the astonishing and frightening claim that 150 million adults out of 400 million in the European Union believe that Israel is conducting a war of extermination against the Palestinians. They accuse the Jewish state of apartheid and ethnic cleansing while referring to Jews as the new Nazis. How did you arrive at this alarming statistic and what proof do you have?  By Gerhard Spörl, Der Spiegel, October 17, 2013 Denmark was the only European country to save almost all of its Jewish residents from the Holocaust. After being tipped off about imminent roundups by prominent Nazis, resisters evacuated the country's 7,000 Jews to Sweden by boat. A new book examines this historical anomaly. They left at night, thousands of Jewish families, setting out by car, bicycle, streetcar or train. They left the Danish cities they had long called home and fled to the countryside, which was unfamiliar to many of them. Along the way, they found shelter in the homes of friends or business partners, squatted in abandoned summer homes or spent the night with hospitable farmers. "We came across kind and good people, but they had no idea about what was happening at the time," writes Poul Hannover, one of the refugees, about those dark days in which humanity triumphed. At some point, however, the refugees no longer knew what to do next. Where would they be safe? How were the Nazis attempting to find them? There was no refugee center, no leadership, no organization and exasperatingly little reliable information. But what did exist was the art of improvisation and the helpfulness of many Danes, who now had a chance to prove themselves. Members of the Danish underground movement emerged who could tell the Jews who was to be trusted. There were police officers who not only looked the other way when the refugees turned up in groups, but also warned them about Nazi checkpoints. And there were skippers who were willing to take the refugees across the Baltic Sea to Sweden in their fishing cutters, boats and sailboats. A Small Country With a Big Heart Denmark in October 1943 was a small country with a big heart. It had been under Nazi occupation for three-and-a-half years. And although Denmark was too small to have defended itself militarily, it also refused to be subjugated by the Nazis. The Danes negotiated a privileged status that even enabled them to retain their own government. They assessed their options realistically, but they also set limits on how far they were willing to go to cooperate with the Germans.  By Roger Moorhouse, New Statesman, October 3, 2013 Review of Hitler's Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, by Wendy Lower, Chatto & Windus, 288pp, £18.99 It’s worth remembering here that many of those women who committed crimes could not resort to the time-worn excuse that they were “following orders”. They were not. The conventional image of women in Nazi Germany is well known. In what was a very masculine world, women generally appear either as hysterical, weeping Hitler fanatics or as hapless rape victims, reaping the Soviet whirlwind. Some readers, however – those familiar with the execrable concentration camp guards Irma Grese and Ilse Koch or perhaps with Bernhard Schlink’s novel The Reader – might recognise a third stereotype: that of the woman as perpetrator. Hitler’s Furies, a new book by the American academic Wendy Lower, brings this latter image to a non-specialist audience. Distilling many years of research into the Holocaust, Lower focuses her account on the experiences of a dozen or so subjects – not including Grese and Koch – ranging from provincial schoolteachers and Red Cross nurses to army secretaries and SS officers’ molls. Despite coming from all regions of Germany and all walks of life, what they had in common was that they ended up in the Nazi-occupied east, where they became witnesses, accessories or even perpetrators in the Holocaust. Lower is scrupulously fair to her subjects, providing a potted biography of each, explaining their social and political background and examining the various motives – ambition, love, a lust for adventure – that propelled them to the “killing fields”. This objectivity is admirable, particularly as most of the women swiftly conformed to Nazi norms of behaviour, at least in turning a blind eye to the suffering around them. One woman, a Red Cross nurse, organised “shopping trips” to hunt for bargains in the local Jewish ghetto, while another, a secretary, calmly typed up lists of Jews to be “liquidated”, then witnessed their subsequent deportation. Most shocking of all are the accounts of the women who killed. One of Lower’s subjects, a secretary-turned-SS-mistress, had the “nasty habit”, as one eyewitness put it, of killing Jewish children in the ghetto, whom she would lure with the promise of sweets before shooting them in the mouth with a pistol. Lower presents another chilling example: that of an SS officer’s wife in occupied Poland who discovered a group of six Jewish children who had escaped from a death-camp transport. A mother, she took them home, fed and cared for them, then led them out into the forest and shot each one in the back of the head.  By Catherine Chatterley Jewish Political Studies Review Review of Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives (Studies in Antisemitism). Published by Indiana University Press, 2013. pp.576 Today, more than sixty years after the destruction of European Jewry, antisemitism is a globalized phenomenon and one that appears to be evolving on a number of fronts. Jew-hatred has a millennial history and is one of humanity’s most complex imaginative systems. Nonetheless, antisemitism remains a subject that is understudied and under-researched in serious scholarly circles and on our university campuses. Alvin Rosenfeld’s new collection of essays, Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives, is the first book in a new series on the subject to be published by Indiana University Press. The book is a pioneering contribution to the burgeoning field of Antisemitism Studies. Composed of nineteen separate essays, the text as a whole clearly identifies antisemitism as a transnational phenomenon, a serious global problem that connects people across cultures and continents, operating through the political spectrum in local, national, and international contexts. Many of the essays are indispensable to our understanding of contemporary antisemitism and how these new manifestations are informed and empowered by classical themes. To give readers a sense of the wide range of subject matter covered in this collection, the authors can be grouped as follows: Bernard Harrison and Elhanan Yakira provide philosophical-analytical reflections on the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism; Alejandro Baer, Zvi Gitelman, Szilvia Peremiczky, and Anna Sommer Schneider address the burdensome weight and contested influence of historical antisemitism on contemporary Spain, post-Soviet Europe, Hungary, Romania, and Poland, respectively; Emanuele Ottolenghi and Ilan Avisar analyze the thorny subject of Jewish participation in anti-Zionist politics; Bruno Chaouat (France), Paul Bogdanor (Britain), and Eirik Eiglad (Norway) cover the debates about the waning of post-Holocaust taboos and a resurfacing of antisemitism in western Europe; in an attempt to understand the roots of Islamized antisemitism several authors uncover past relationships between Muslim religious and Jihadist movements and the influence of western fascist and communist ideologies on each of them (Robert Wistrich, Matthias Küntzel; Jamsheed K. Choksy, Rifat Bali, and Gunther Jikeli); Dina Porat and Alvin Rosenfeld focus attention on the complex and disturbing relationship between the Holocaust and contemporary forms of antisemitism; and, finally, Tammi Rossman-Benjamin theorizes on the relationship between ethnic studies and antisemitism at San Francisco State University. Due to the constraints of space, this review will focus attention on several of this collection’s outstanding contributions. For those readers interested in the dynamic of continuity between classical antisemitism and new variations, Alejandro Baer’s work on Spain stands out as a profoundly important commentary on the uniquely persistent and obsessive nature of antisemitism and its roots in the European religious imagination. In an essay entitled, “Between Old and New Antisemitism: The Image of Jews in Present-day Spain,” Baer argues that the negative religious caricature of Jews remains “firmly anchored” in Spanish cultural memory through language, literature, and popular tradition, despite the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492. “The Jew” haunted Spanish discourse through the nineteenth century, and themes of supposed Jewish criminality and conspiracy were used in nationalist propaganda during the Civil War (1936-1939) and under Franco’s dictatorship, which ended in 1975. Biological racism did not operate in Francoist fascism in the same way or to the same degree as that of Nazism. Baer explains the strange schizophrenic attitude toward Jews under Franco where the regime maintained a traditional hatred of Jews and Judaism and ignored the Holocaust after the war, while at the same time boasting about having saved Jews. Sephardic Jews were allowed into Spain in the 1950s and 1960s, and synagogues were even established. Nonetheless, Spain did not recognize Israel until 1986, making it the last European country to take this step. Baer clearly sees a connection between traditional Spanish Catholic bias against Jews and contemporary hostility toward Jews and the State of Israel, which is well documented by recent survey data (2009) showing that 46% of the Spanish population rate Jews unfavorably and 74% admit that Israeli actions negatively affect their view of Jews. Baer’s essay clearly demonstrates that traditional antisemitism can and does determine contemporary perceptions of Jews and the Jewish state. Baer suggests that Charles Glock’s “consequential” dimension of religion is alive and well in today’s Spain. How this operates in other post-Christian contexts is an important question to be investigated. Zvi Gitelman’s study of “Comparative and Competitive Victimization in the Post-Communist Sphere” is crucial to our understanding of the “double-genocide” argument and dual-memory culture at work in the former Soviet Union. Of particular significance to the arguments that attempt to equalize Nazi and Soviet crimes in the new states of Eastern Europe is the myth of the Zydokomuna (Jewish Communist). Gitelman evaluates membership numbers in the communist parties of Poland, Hungary, Romania, Latvia, and Lithuania and concludes that, while Jews did constitute a disproportionate number of communists, the number of communists among Jews was miniscule (less than a tenth of one percent in Poland, for example). Nationalists in these new independent states use the accusation of “Jewish-Communism” as a way to rationalize and excuse the negative record of collaboration with Nazi Germany and their own local violence against Jewish neighbors. Thus, if Jews effectively can be made responsible for the crimes of communism, their suffering in the Holocaust can be both minimized and justified, and the complicity of Eastern European populations in their mass murder can be legitimized. Gitelman argues that the Soviet Union did not attempt to destroy groups of people in their entirety and therefore did not perpetrate genocide on any of the peoples of Eastern Europe. According to Gitelman, the double-genocide thesis, then, is a false construction, which has more of a political and strategic underpinning than one dependent upon the actual historical record. Several scholars address the Holocaust in this collection. In the closing essay of the book, Alvin Rosenfeld argues convincingly that the recent resurgence of antisemitism has caused serious collateral damage to the memory and history of the Holocaust. Thus, the memory of the Holocaust can no longer be assumed to offer protection against the return of antisemitism. He observes not only a well-documented increase in Holocaust denial and distortion but also provides examples of genocidal rhetoric promising a so-called “Second Holocaust.” The promise to “wipe Israel off the map,” where almost half the Jews of the world reside, is almost a cliché in today’s world—something we are now too accustomed to hearing. Rosenfeld concludes that this incredibly disturbing post-Holocaust reality must be addressed so as to prevent a future catastrophe, but first we must begin to understand and interpret genocidal rhetoric as threatening. Given the recent past, he suggests, words matter, especially those used by political and religious leaders. Why, after Auschwitz, this basic lesson has not been learned is a serious question indeed. The ideological and political connections between Europe and the Middle East are also important to our understanding of contemporary antisemitism, especially that of the Islamic world. It is crucial that we examine the Western pathways through which antisemitism entered the Arab world, as well as how and why a European phenomenon has been Islamized for consumption in the Middle East. One of the most difficult debates in the field of contemporary antisemitism involves the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. Here, the essays by Bernard Harrison, Elhanan Yakira, and Robert Wistrich are particularly helpful. Emanuele Ottolenghi’s essay on the awkward but revealing subject of the intra-Jewish conflict at the heart of current public debates about antisemitism also deserves mention. There can be no question that the fraternal aspect of this conflict over ideas and interpretation accounts partly for the highly emotional and sometimes ad hominem nature of debates in the field of Antisemitism Studies. Our conversations today about contemporary antisemitism, especially the manifestations that involve Israel and Zionism, inevitably connect to combustible questions about Jewish identity and contested definitions of Jewish authenticity. Antisemitism, like any persistent form of human hatred, must be subjected to rigorous scholarly analysis so that human beings develop a concrete understanding of its history, nature, and the reasons for its broad and continuing appeal. Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives is a key text that helps to frame the intellectual debates now developing in the field of Antisemitism Studies and as such it has the potential to help move the field forward intellectually, something which is indeed crucial at this moment in time. Catherine D. Chatterley is the author of Disenchantment: George Steiner and the Meaning of Western Civilization After Auschwitz (Syracuse, 2011), which was a National Jewish Book Award Finalist in Modern Jewish Thought. She teaches modern European and Jewish history at the University of Manitoba and is the founding director of the Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism (CISA). She can be reached through the Institute’s website: canisa.org. This book review has been made available courtesy of the Jewish Political Studies Review.  Yad Vashem Mourns the Passing of Eminent Holocaust Historian Prof. Israel Gutman, survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto and Auschwitz who testified in the Eichmann trial and was a trailblazing historian of the Holocaust. (October 1, 2013 – Jerusalem) Yad Vashem is saddened by the death of Prof. Israel Gutman, a survivor of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and Auschwitz who was a leading and trailblazing historian of the Holocaust in Israel and abroad. Prof. Gutman passed away last night (October 1, 2013), in Jerusalem at the age of 90. Prof. Gutman, was among the founders of the Yad Vashem International Institute for Holocaust Research, and lived in Jerusalem. A widower, he is survived by two daughters, and 3 grandchildren. The funeral will take place tomorrow in Jerusalem. Yad Vashem Chairman Avner Shalev said: "My mentor and friend, Professor Israel Gutman, made a deep impression on historiography in Israel and around the world, and made a significant and unique contribution to the propagation of historical awareness regarding the Holocaust and its meanings among the wider public forum in Israel, especially among the youth. Professor Gutman's personal resume – as someone who experienced in the flesh the horrors of the Holocaust, fought in the Warsaw ghetto, was imprisoned in Auschwitz and was a member of the camp's Jewish underground, survived the death marches and was a witness to all that occurred – added an enormous weight to his rare and exceptional strength as a researcher, teacher and leader. We will miss his insight and his friendship.” Israel Gutman was born in Warsaw in 1923. His parents and older sister died in the ghetto, and his younger sister was a member of Janusz Korczak’s orphanage. As a member of the Jewish Underground in the Warsaw ghetto, Israel Gutman was wounded in the uprising. From Warsaw he was taken to Majdanek, and from there to Auschwitz. In May 1945 he was sent on the death march to Mauthausen. Gutman spent two years in the camps. After the war, he helped in the rehabilitation of survivors, was active in the Bericha movement, and immigrated to Eretz Israel in 1946. He joined Kibbutz Lehavot Habashan where he raised a family and was a member of the kibbutz for 25 years. In 1961 he gave testimony during the Eichmann trial. In 1973, Prof. Gutman moved to Jerusalem, and in 1975 received his Ph.D. from the Hebrew University for his thesis The Resistance Movement and the Armed Uprising of the Jews of Warsaw In the Context of Life in the Ghetto, 1939-1943. Beginning his academic career at the Hebrew University, he later headed Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Department for the Study of Contemporary Jewry, (1983-1986). He was a visiting professor at UCLA in 1980-1981. Gutman retired from Hebrew University in 1993. At the same time, Gutman was a leader and an integral part of the research activities at Yad Vashem. From 1993-1996 he headed the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem, of which he was a founder. Between 1996-2000 he served as Yad Vashem’s Chief Historian. Since 2000 Prof. Gutman was an Academic Advisor to Yad Vashem. He was a member of the Yad Vashem Council, the International Institute for Holocaust Research’s administration, Yad Vashem’s Scientific Board, and a member of the editorial staff of Yad Vashem Studies. He was also a founder of Moreshet, A Testimonial Center in memory of Mordecai Anielewicz, and Deputy Chairman of the International Auschwitz Council. One of his main projects was the comprehensive and groundbreaking Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. He published many works on the Holocaust, including The Jews of Poland Between Two World Wars; Unequal Victims: Poles and Jews During World War Two; The Jews of Warsaw, 1939-1943; Resistance: The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising; Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp; and Nazi Europe and the Final Solution. Some of the numerous awards his work has received are the Salonika Prize for Literature, the Yitzchak Sadeh prize for Military Studies, and the Polish Unification Prize. Gutman received honorary doctorates from Warsaw University in 1995 and from Brandeis University in 2009. Yad Vashem Chairman Avner Shalev said: "Professor Gutman achieved academic success with social and cultural ramifications that cannot be overstated: he gave legitimacy and even a historiographical centrality to the Jewish point of view regarding the Shoah. Professor Gutman succeeded in making "room" in the world of research for the experiences, positions and points of view of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, so that their voices would achieve the consideration and attention they deserved. "From the end of the 1970s, when his position as a leading researcher of the Holocaust and Polish Jewry had been established, as well as his central role among the "scholars of Jerusalem," Professor Gutman turned towards a new horizon of activity: creating active scientific contacts between Israeli Holocaust research and that taking place abroad. He achieved this through, among other things, international research conferences, which he pioneered, and which, together with the publications that came in their wake, were cornerstones of Holocaust research. Professor Gutman invested a great deal of effort into nurturing scientific contacts with Poland. Even during the Communist era, the Poles accepted much of his critiques, and he became a greatly valued guest (the University of Warsaw even awarded him an honorary doctorate). In his research on the Warsaw ghetto, Professor Gutman established his position at the forefront of Holocaust research, and attained international acclaim. His research on the ghetto was the point from which his academic writings broadened into a range of basic Holocaust-related issues: resistance, the Zionist youth movements, the Judenrat, Jewish forced labor, Jewish-Polish relations, the uniqueness of the Holocaust, the social aspect of the camps, and more." For more information about Prof. Gutman’s life, research and writing, including testimony: http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/survivors/gutman.asp. |

CISA Blog

This blog provides selective critical analysis on developments in contemporary culture related to the subjects of antisemitism, racism, the Holocaust, genocide, and human rights.

|

© 2025 Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism. All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed