|

To the Editor of the Winnipeg Jewish Review:

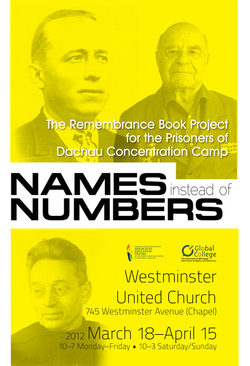

Catherine Chatterley’s essay in the Winnipeg Jewish Review of March 24th, “The Holocaust was not an Interfaith Experience,” is a succinct and brilliant summary of what the Holocaust actually was. It’s important because it presents history accurately. But it’s even more important because, by presenting that history accurately, it help correct the growing effort to universalize it—to make it into a lesson about “man’s inhumanity to man.” Needless to say, many experiences provide such a lesson. But the Holocaust was unique in its methods and in its ferocious focus on Jews—a focus the sentiment behind which is some two thousand years old and has resulted in numerous spasms of murder in the places where Jews have lived. Nor did the Holocaust end this sentiment. Rather, its massive ferocity left antisemitism temporarily exhausted; after the Holocaust, antisemites couldn’t express their bigotry quite as easily in polite company, at least for a few decades. It was almost as if antisemitism in its active form had taken a kind of vacation. But active antisemitism is back and, with increasing speed it’s racing around the world. It’s being expressed increasingly in Europe, and with blood-curdling intent and language in the Arab/Muslim world. Nor is it absent in Canada or the United States. Dr. Chatterley’s essay trenchantly demonstrates the historical truth of antisemitism’s lethal consequences during the Holocaust—the truth that the Holocaust—the Shoah--was, indeed, not an interfaith experience but the most intense example of a specifically antisemitic experience. And it provides an important corrective to the increasing tendency to universalize the Holocaust, which is done not only by well-meaning non-Jews but also by well-meaning Jews. Both of these groups fail to undertand how the distortion of historical memory corrupts its power to teach. Both of these groups recognizes that if, in the effort to teach universal values, a particular historical experience is expanded to teach universal lessons, then the particular lesson that it can teach so clearly—the murderous consequences of antisemitism—is lost. In writing her important essay, and in founding the Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism, Dr. Chatterley has done a great service not only to the memory of the Holocaust dead but also to humanity itself. And her essay—and the Winnipeg Jewish Review—have done a great service to the Jews of the present and the future. It’s the kind of accurate Holocaust memory that she teaches that has a chance of reducing the likelihood that yet another Holocaust—this time carried out not by Germans but by others, not in Europe but in the Middle East, and not by gas chambers but by nuclear weapons—will follow. Walter Reich is the Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Professor of International Affairs, Ethics and Human Behavior at The George Washington University and a former Director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.  By Dr. Catherine Chatterley Founding Director, CISA Adjunct Professor of History, University of Manitoba The Dachau concentration camp display entitled Names Instead of Numbers [currently in Winnipeg] is not a Holocaust exhibit. The victims of the Hitler regime were indeed diverse but the victims of the Holocaust were Jewish. This is a fundamental distinction and one that requires further elaboration given recent press coverage (see links below). It should be mentioned that the German creators of the exhibit do not promote their display as a Holocaust exhibit but as an exhibit about National Socialism: http://www.gedaechtnisbuch.de/namen-statt-nummern/english/index-engl.html Three groups of people were slated for extermination under Nazism: the disabled of Germany from October 1939 throughout the war years with a brief cessation from August 1941-August 1942; the nine million Jews of Europe and of all future German occupied territories (we know today that Hitler promised to annihilate the Jews of the Islamic world as well); and the Romani people (better know by the pejorative term “Gypsy”), whom Himmler added to the already existing extermination campaign against the Jews in December 1942. Antisemitism was the central motivating factor of Hitler’s racist policies and of his war of aggression against his neighbors. Hitler believed that communism was a Jewish conspiracy, which worked in tandem with other aspects of a larger “International Jewish Conspiracy” to rule the planet and to destroy Germany. His war of annihilation against Stalin was a war against the Jews and what he termed Judeo-Bolshevism. Under the umbrella of World War II, Hitler unleashed a massive racist engineering project upon Europe, in which the Slavic peoples would be reduced to a slave population to work vast tracts of the new Germania, where there would no longer be any Jews or Roma, and where “racially pure” German women would birth perfect “Aryan” soldiers for the Reich. Before Hitler could unleash a continental war, however, he had to consolidate his power inside Germany. With this in mind, he focused on building his volksgemeinschaft (community of the people) and won enormous support from the German people for his dedication to their social welfare, re-employment, and national pride after the catastrophe of WWI. One of the first things Hitler did to consolidate his power was to create a system of prisons, or concentration camps, and Dachau was the first one to be opened in March 1933. Dachau Dachau was a political prison camp that housed Germans who were arrested and sentenced by the regime for political crimes. The first prisoners were socialists, communists, and the odd monarchist, all of whom were anti-Nazi and about 10% also happened to be Jewish. In 1936, other political prisoners (clergy and Jehovah’s Witnesses) and non-political prisoners (Roma, gay men, vagrants, prostitutes, habitual criminals) were incarcerated in Dachau. Thirty-six thousand Jews were arrested on November 9-10, 1938 during Kristallnacht and 11,000 of them were sent to Dachau, most of whom were released after signing declarations that they would leave Germany. Once the decision was made to exterminate Europe’s Jews, the Jewish prisoners in Dachau and other concentration camps were deported to their deaths in the East. Jewish POWs from Eastern Europe were placed into Dachau and its subsidiary slave labor camps during 1944, and made up about 30% of its inhabitants when the American army liberated the camp on April 29, 1945. Dachau held 206,206 prisoners in its twelve-year existence and 31,591 prisoner deaths were registered. Mass shootings, medical experimentation, and slave labor were features of this particular Nazi camp. The Holocaust Hitler’s anti-Jewish policies were unleashed within days of his appointment as Chancellor. His tactics evolved over time, beginning with social isolation and enforced emigration for German Jewry from 1933-1939. Once engaged in a war with Europe, and faced with millions of Jews under his control, Hitler planned for their removal, first to the far reaches of the eastern end of the Reich, then to the island of Madagascar. That plan was finally abandoned when he failed to cow the British into submission in September 1940. He forced the large Jewish populations of Eastern Europe into over 1,100 ghettos and sealed them from the outside world. With the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, Hitler made the decision to exterminate European Jewry, and this process began immediately with the mobile killing units of the Einsatzgruppen, who followed the German army into Eastern Poland and the USSR. After experimenting on Jews with a number of killing methods, the Germans settled on an industrialized assembly line process and built six death camps in Poland for the specific purpose of exterminating the Jews of Europe. The most lethal death camp was Auschwitz-Birkenau, which is the largest killing site in recorded history and is a historical novum. Never before or since has a state designed, built, and maintained factories for the deception, murder, gassing, and burning of (Jewish) babies, children, women, and men. Never before or since has the world seen the establishment of a small city of about 45 square kilometers (approximately 1/10th of the size of Winnipeg) surrounded by 45 satellite slave labor camps built for the dedicated purpose of annihilating an entire people. Never before or since has the world seen a human killing facility that at peak capacity (in May of 1944) was murdering 10,000 Jews every day. The clothing and belongings of these individuals were recycled and dispersed among the German population (the mountains of clothing, suitcases, razors, eyeglasses, brushes, children’s toys, prosthetic limbs), their hair was shaven and used to stuff German mattresses, their bones and ashes used as fertilizer. Then there are the Jews who were reserved for so-called medical experimentation, whose body parts were sent back to scientists in Germany. Between May 1940 and February 1945, just over 1.1 million people were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau, one million of whom were European Jews. The remaining 100,000 include approximately 74,000 Poles; 21,000 Roma; 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war; and 10,000-15,000 members of other European nationalities (Soviet civilians, Czechs, Yugoslavs, French, Germans, and Austrians). Deaths during the Nazi period for other groups mentioned are as follows: 1.9 million Polish civilians died under German occupation and racial policies; 1,400 Jehovah’s Witnesses died in the camps and 250 were executed by the military; the Nuremberg Trials puts the killings of German disabled people at 275,000; between 5,000-15,000 gay men; and 220,000 Roma. Over 6.3 million Jews were murdered across Europe by the Nazi regime and its collaborators during WWII. Ironically, in this case, numbers do tell the story. With so many cultural and political pressures working today to erode, erase, and distort the very specific history and meaning of the Holocaust, we must re-dedicate ourselves to resisting these trends and to teaching Canadians the truth about the past. Links to press coverage: http://www.christianweek.org/stories.php?id=1923 http://winnipeg.ctv.ca/servlet/an/local/CTVNews/20120318/wpg_westminster_holocaust_120318/20120318/?hub=WinnipegHome http://www.cbc.ca/manitoba/scene/events/2012/03/19/holocaust-exhibit/ http://www.therecord.com/news/canada/article/688590--names-instead-of-numbers-winnipeg-church-hosts-travelling-holocaust-exhibit http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/local/exhibit-gives-names-back-to-nazis-victims-143286546.html http://www.winnipegfreepress.com/our-communities/metro/Church-hosts-Dachau--concentration-camp-exhibit-142517615.html?viewAllComments=y Ha'aretz, by Yehuda Bauer, March 12, 2012

There is a similarity, of course. The Nazis' racist anti-Semitism eventually developed into an explicit desire to completely annihilate the Jewish people. And the Iranian leadership talks about the global Jewish enemy, though it is willing to make an exception for Jews who accept its authority (Iran's Jewish population, Haredi extremists who agree to cooperate with Tehran and the like ). This is where the similarity ends. In the 1930s and '40s, the Jewish people was almost entirely powerless. Evidence of this can be found in the internal documents of Great Britain's Foreign Office and the U.S. Department of State. In the best case, Jews were seen as pathetic people who could not be helped; in the worst, they were seen as an unnecessary burden, as illustrated by a telegram sent by Britain's Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Richard Law to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden on March 18, 1943: "I am sorry to bother you about the Jews. I know what a bore this is." In January 1944, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt established the War Refugee Board and gave it wide-ranging powers. The board tried to take action, but nearly all its funding came from American Jews, not the government, and its achievements were negligible. Today, in contrast, there exists a Jewish state that has become a regional power, and U.S. Jews have profound influence in American politics. While it is true that Israel, for all its boasting, cannot protect all of the world's Jews, it can play a significant role in these efforts. During the Nazi era, there was no consideration of the Jews as a genuine force. Today there is a consensus in the United States and Canada, as well as in Europe, that Israel's existence and security must be protected. True, this acknowledgment is not without its problems and may be incomplete, but 70 years ago it was completely absent. Could it happen again? Absolutely not, because Jews are no longer powerless. Contrary to Netanyahu's claims, Iran's nuclear facilities are not the same as Auschwitz. Is it possible to drop an atomic bomb on Israel? Of course it is possible. And our friend, Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, would do so if he could. Of course, an error of one degree or less would end up destroying Jerusalem's Al-Aqsa mosque, and the bomb issue has more to do with the Iranians' desire to control the petroleum reserves of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states than a credible threat to Tel Aviv - although this cannot be discounted. Still, this is very different from going helplessly to the gas chambers. It is a different situation. Then, it was impossible to stand up against what was being done to the Jews. Today Jews have options, including military ones. The analogy is false, demagogic and infuriating, and it is more dangerous for us than it is for the Iranians. Any air strike against Iran, God forbid, will be the result of an Israeli decision. It will wreak uncontrolled disaster and delay only briefly the manufacturing of an Iranian bomb. Bombing Iran, not Iran's bomb, could destroy Israel. There is no analogy. Professor Bauer is a member of CISA's Academic Council New York Times, by Dennis Hevesi, March 13, 2012 Peter Novick, a history professor at The University of Chicago who stirred controversy in 1999 with a book contending that the legacy of the Holocaust had come to unduly dominate American Jewish identity, died on Feb. 17 at his home in Chicago. He was 77. The cause was lung cancer, his wife, Joan, said. Dr. Novick — “a nonobservant Jew,” according to his wife — was the author of “The Holocaust in American Life,” in which he asked why the Nazi genocide had “come to loom so large” and “whether the prominent role the Holocaust has come to play in both American Jewish and general American discourse is as desirable a development as most people seem to think it is.” He was skeptical that it was, and 10 years of research, he added, “confirmed the skepticism.” Dr. Novick did not deny the enormity of the Holocaust or suggest that it should be forgotten. But he contended that at a time of increasing assimilation, intermarriage and secularization, it had become “virtually the only common denominator of American Jewish identity in the late 20th century.” The Holocaust, as he saw it, was also being used for political ends. That was particularly true, he said, after the Six-Day War in 1967 and the Yom Kippur War in 1973 had heightened fears of Israel’s vulnerability. “After 1967, and particularly after 1973, much of the world came to see the Middle East conflict as grounded in the Palestinian struggle to, belatedly, accomplish the U.N.’s original intention” of creating two states, he wrote. “There were strong reasons for Jewish organizations to ignore all this, however, and instead to conceive of Israel’s difficulties as stemming from the world’s having forgotten the Holocaust. The Holocaust framework allowed one to put aside as irrelevant any legitimate grounds for criticizing Israel.” Dr. Novick’s book drew wide and varying reactions from reviewers and academicians. In his review of the book in The New York Times, Lawrence L. Langer, a scholar of Holocaust literature at Simmons College in Boston, was unconvinced by Dr. Novick’s contentions. “Novick rightly slights formulaic responses to the Holocaust,” he wrote, “from the ubiquitous but vacuous ‘Never again!’ to the periodic manipulations of popular sympathy by some Jewish organizations when they fear a rise in anti-Semitism or a decline in support for Israel. But the abuse of the Holocaust for political or emotional ends does not discredit the continuing significance of the atrocity itself, as a human catastrophe and an example of vast evil in our time.” Eva Hoffman, the writer and literary scholar, writing in The New York Review of Books, was more supportive. She noted that the book had been “criticized for the harshness and alleged ‘cynicism’ of its tone” and acknowledged that it was “indeed a tough-minded work, sharp, brusque, and sometimes nearly Swiftian in its acerbities.” But, she added, “the anger is a measure of Novick’s involvement; his candor is part of the argument. Novick is clearly intent on cutting through the circumlocutions of habitual Holocaust discourse, on challenging what he sees as its obfuscations with uncompromising logic and saying out loud what is often intimated in private.” Jan Goldstein, a friend and colleague of Dr. Novick’s at the University of Chicago, recalled that “very often historians of Jewish background would take the thesis as an attack on American Jews.” “He was regarded by some as a self-hating Jew,” Dr. Goldstein said of Dr. Novick, “which he was definitely not.” In 2000, The Economist cited Dr. Novick’s book as the “starting point” for a far more controversial one, “The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering,” in which the author, Norman G. Finkelstein, contended that the Holocaust was being exploited for personal, political and economic reasons. Ms. Novick recalled the uproar over her husband’s book. “Some people hated the book,” she said. “People said: ‘This is a bad thing. You’re saying the Holocaust was not the most horrible thing in the world.’ ” Still, she added, “Unbeliever that he was, Peter found strong supporters among many rabbis — liberals to Orthodox — who shared his concern that the Holocaust might replace religion as the central symbol of Jewishness.” Peter Novick was born in Jersey City on July 26, 1934, to Michael and Esther Novick. His grandparents immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe in the 1890s. After serving in the Army, Dr. Novick received his bachelor’s degree in 1957 and his doctorate in 1965, both from Columbia University. Besides his wife, he is survived by a son, Michael. Dr. Novick joined the University of Chicago faculty in 1966 and retired in 1999. His specialty was historiography, the study of the techniques of historical research, and even here he challenged orthodoxies. In his 1988 book, “That Noble Dream: The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession,” he questioned the idea of objectivity itself in historical research. Tracing its development, he wrote that history was long considered a kind of literary genre until the late 19th century, infused with an author’s point of view. That changed when the prevailing ideal became fact-based documentation without preconception. Dr. Novick was again skeptical, believing that the “myth of objectivity breaks down,” as Dr. Goldstein put it — “that there is no such thing as a fact in isolation from a preconceived theory or narrative.” Of the criticism of his Holocaust book, Dr. Novick told the Chicago Tribune in 1999: “I knew I’d get some static and controversy on this,” adding that the reaction was “divided between those who say, ‘Right on!’ and those who are scandalized and outraged.” “They don’t just pay me here for the teaching I do,” he said. “I produce scholarship.” |

CISA Blog

This blog provides selective critical analysis on developments in contemporary culture related to the subjects of antisemitism, racism, the Holocaust, genocide, and human rights.

|

© 2025 Canadian Institute for the Study of Antisemitism. All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed